Transforming Minnesota's Public Health System

- Home: System Transformation

- About This Work

- Framework of Foundational Responsibilities

- Definitions, Criteria, and Standards for Fulfillment

- Joint Leadership Team

- Minn. Infrastructure Fund and Local Innovation Projects

- Governance Groups and Communities of Practice

- Data Modernization

- Regional Data Models

- Tribal Public Health Capacity and Infrastructure

- FPHR Grant: Funding for Foundational Responsibilities

- Reports, Fact Sheets, Resources

- Newsletter

- Message Toolkit

Related Sites

Contact Info

Public Health System Transformation Update Newsletter

September 2025 | View all system transformation newsletters

Innovation, data, and partnership go hand in hand in hand

Public health’s “eureka” moments are well known, at least among those of us working in public health—Alexander Fleming accidentally discovering penicillin in a moldy petri dish, Edward Jenner lancing actual smallpox-filled pus from someone’s hand and injecting it into somebody else, John Snow pulling the handle from the water pump and almost single-handedly ending London’s 1854 cholera outbreak (if we’re honest, he probably had to use two hands; a cast iron pump handle is pretty heavy).

Dig a little deeper, though, and every fantastic public health discovery is firmly embedded in—and inseparable from—mounds of surrounding data, from months or years or sometimes decades of investigation.

Alexander Fleming in his laboratory. Photo credit: Mary Evans Picture Library Ltd.

Alexander Fleming’s work on penicillin echoed centuries of knowledge across history and geography in using plants and fungi to treat infection. His findings languished, though, until an Oxford lab team conducted lab trials and field experiments to amass the replicable data that could show success.

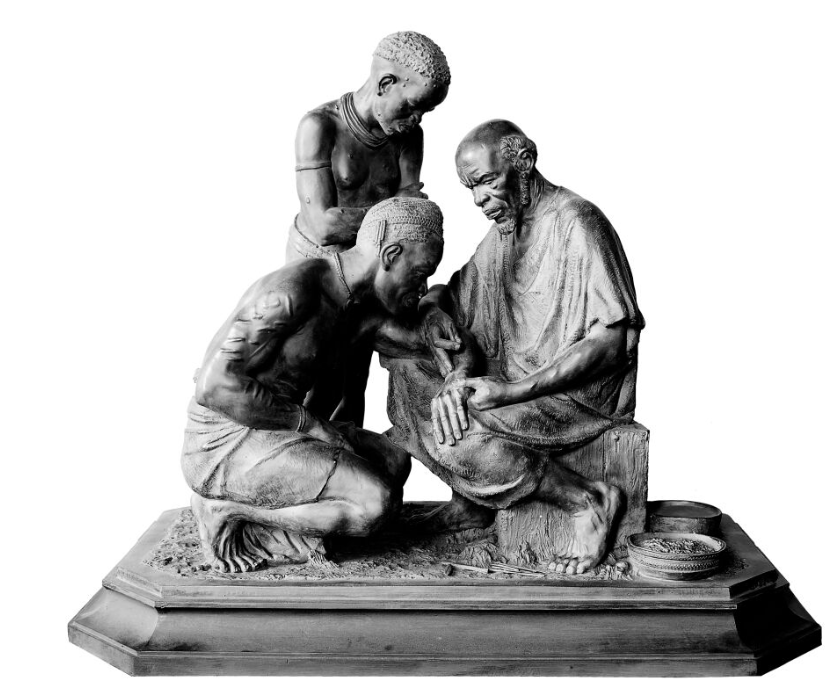

A plaster model of three men from Djen, Nigeria, one of whom is being inoculated against smallpox, by Jane Jackson. Photo credit: The Wellcome Collection.

Edward Jenner wasn’t the first person to inoculate others against diseases like smallpox—but he was one of the first to publish his gathered data on inoculation, and do so in English. Deliberately inducing immunity against infectious diseases was practiced for centuries in Africa and China before Jenner published, and Jenner and his contemporaries directly learned from and built on that often (but not always) unwritten data and knowledge.

An excerpt of a map of London’s Soho district, created by John Snow.

Before the handle came off of the Broad Street water pump, John Snow mapped cholera morbidity and mortality around many of the city’s water pumps, compared microscopic water samples, and analyzed mortality in areas served by different waterworks to show how upriver residents with cleaner water were less likely to die of cholera.

Data shows us where public health interventions succeed, however sudden they seem.

Minnesota’s regional models to collect, use, and share local population health data will help provide the staffing, knowledge, expertise, skills, and necessary infrastructure to increase an entire region’s ability to access, collect, use, manage, and share population health data. A strong public health data infrastructure across Minnesota means that, no matter where you live, your local health department can make data-driven decisions to meet your community’s health needs and priorities.